Setting Priorities (or, How I Learned to Finally Finish This Essay)

In This Article

-

Usually, I’m good at hiding my half-done priorities, but not everything can be swept aside or pushed into a closet.

-

Little children are hardwired to not think about the world around them (as newborns, we think things stop existing when they leave our field of view).

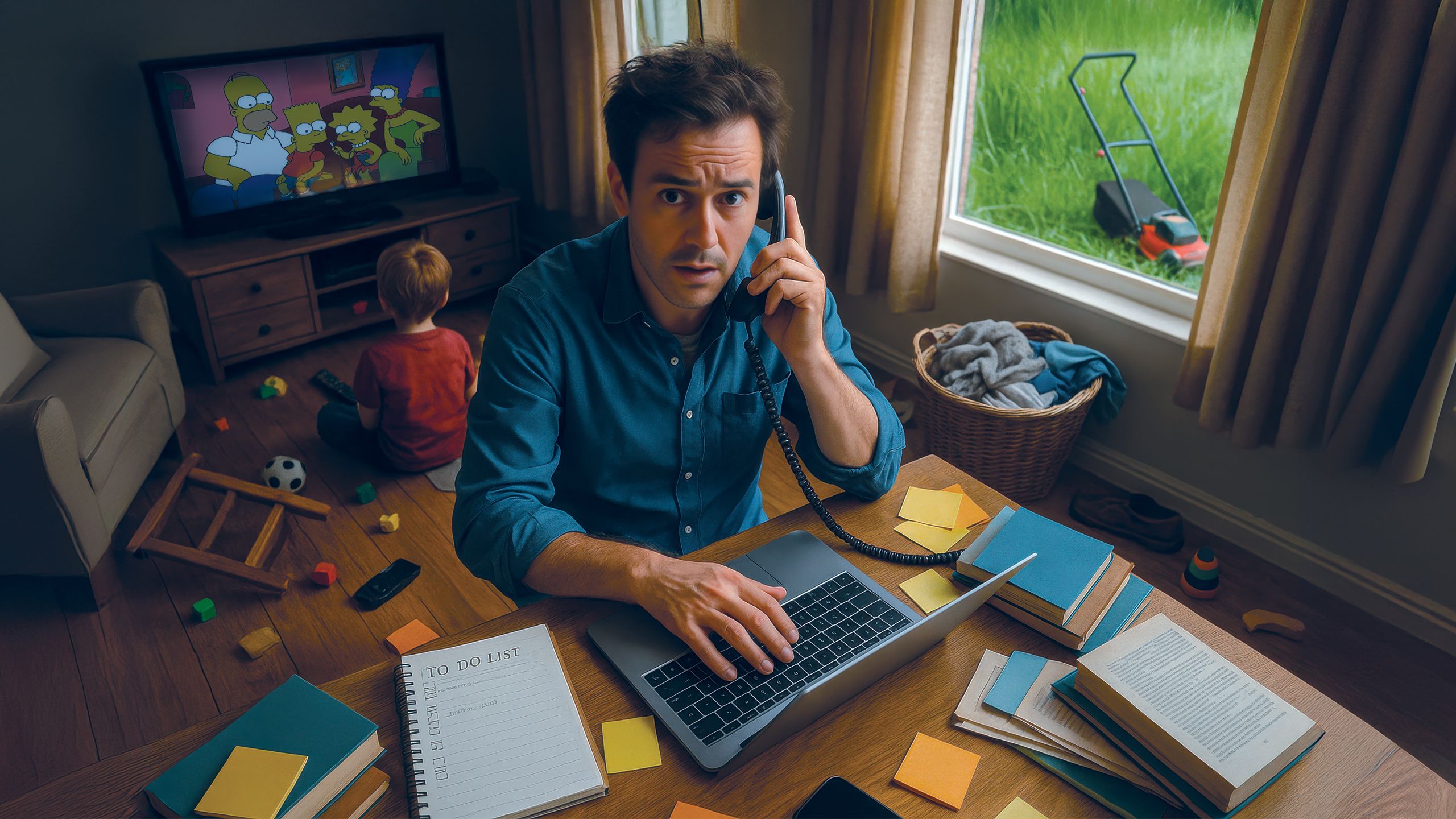

On a less than memorable episode of The Simpsons, Bart, the hell-raising ten-year-old, is struggling to begin a paper on World War I that is due the next day. Books are piled on his desk. The pen is in his hand, touching the paper (back when kids still wrote essays by hand). He looks around the room and sees an especially inviting book on his bookshelf.

“Oh, algebra,” he says excitedly. “I’ll just do a few equations…”

He then hits himself to refocus.

Everyone finds the gag relatable: a task so difficult or boring, with a deadline looming, where the distraction of doing math equations is not only tempting but preferable.

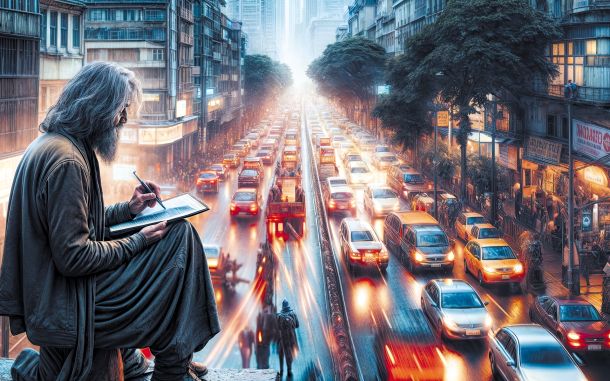

I have no algebra books in my home, but plenty of other distractions that stand out and glitter like half buried pearls. Laundry that suddenly needs doing or trying to decide which is the perfect way to organize my bookshelves (by color? alphabetically?). There are the kinds of distractions that announce themselves randomly and demand my attention. My son deciding he’s hungry ten minutes after refusing lunch. My mother calling with the vague, dreaded, “are you busy right now?” Making sense of what it was I wanted or was supposed to be doing after all of these detours can take more mental energy than I’m capable of, which means I often leave everything unfinished.

Usually, I’m good at hiding my half-done priorities, but not everything can be swept aside or pushed into a closet. My lawn, for instance, is something everyone can see as the result of these shifting priorities. The grand list of plans to repair and care for my lawn every spring has now increased to where the grounds crew of Yankee Stadium would find it difficult. To get rid of all the overgrown bushes and tree branches would take a full weekend, but didn’t we want to take my son to the aquarium? Wasn’t getting him out of the house and away from the TV important? Mowing the lawn itself takes at least two hours, yet my mother isn’t well enough to go grocery shopping on her own. She can’t go without food, right? I can’t put it off, not when I’m supposed to be seeding all the empty patches and pulling out the dandelions and spraying deer repellent. An unending stream of guilt causes me to lurch one way then another, leaving my lawn a mess, an outward expression of things left half-finished or completely unstarted.

The secret, as we are told by various self-help gurus online and daytime talk show hosts, is to put aside the things that aren’t important and embrace the things that are. This is meaningless gobbledygook that looks good on the kind of cheap coffee mugs you see in greeting card stores. If the slogan was “do what makes you happy,” or “prioritize the good in life!” it would have just as much meaning and probably as much impact. The definition of what makes something important is too vague, too changing. After all, each distraction blares its importance to you like a screaming baby. Rather than limit things to important or not important, the best method for avoiding distractions is to prioritize everything. From restocking the scotch tape dispenser to fleeing a house fire.

Discovering that hierarchy is the real trick, and it is a process. Little children are hardwired to not think about the world around them (as newborns, we think things stop existing when they leave our field of view). When we age, our priorities change. Hopefully for the better, but not always. Some people need a lot of time and experience to help learn what’s most important. And even as you figure it out, the distractions come fast and hard. Every week a person is recommended to watch a new TV show, even though they probably haven’t finished watching the latest hit everyone’s talking about. Then comes the dilemma: should that person stop the old show and pick up the new one? What if they’re someone who never skips a Sunday crossword puzzle? Do they continue to do them and watch TV, knowing they might put off work they brought home from the office? When do they get around to paying bills? Calling up their parents to catch up? All these options just from having one show introduced to us.

By the time you’re a young single adult, it becomes easy to think that whatever makes you happy is what’s important. For a long time, my biggest concern was how to be a rock star even though I spent my high school years playing trombone. Once I was out of college and that dream was as realistic as eating unicorn steaks, I went ahead and started waiting tables. All that mattered to me at that age was whether I would walk out of each shift with enough to pay off the essentials. These consisted of gas, rent, and food, not always in that order. Often the food came from McDonald’s and the refreshments from local bars. But happiness was the goal, not nutrition. As long as I wasn’t too picky about it all, I managed to make it work. I was satisfied.

When I started working as a teacher my own happiness depended on others. Staff members needed help. Students wanted feedback from me. The distractions and the goals I needed to accomplish were so numerous it became dangerous to my career to leave some incomplete. I learned early, though not as early as I should have, to prioritize what mattered without leaving everything undone. There were too many days scrambling to finish lesson planning five minutes before the students walked in. Too many mornings struggling to discuss the merits of The Great Gatsby while feeling far from clear-headed. The less said about the burgers that contributed to my expanding waistline the better. It would be wonderful if people learned this earlier in life. But a lot of people don’t. Some never learn to prioritize at all. Judging by how many people still take on Tik Tok challenges, it stands to reason people are not always acting with their best interests (judging by how many challenges there are, there are never too many distractions either).

The vast majority of people also learn that once you have a spouse or partner and children who count on you, or extended family that needs help, their safety and security becomes the most important thing. Something in my lizard-brain activated once I held my newborn son for the first time, a little voice that said, “This thing matters. It’s counting on you.” After that, my brain took all the stimuli around me and, like a badly kept 90s desktop computer, put everything it receives through a quick analysis: on one side, that nagging distraction that demands attention; on the other, my wife and son.

The system isn’t perfect, of course. Sometimes it says that nagging thing is my son, and my brain therefore questions how long I can go and ignore it. The effect is doubled when the request is something innocuous, like demanding we do the same dinosaur puzzle for the sixth time in a row. (Ignoring him is a generally all-around terrible thing to do – newborns and toddlers have to be dealt with eventually if you ever want to get five consecutive seconds of peace).

Ignoring my responsibilities to myself for too long, like any engine that burns too hard for too long, causes me to crash. When things come up that relate only to me – a new videogame demanding my attention, some of my friends making plans to unwind after work, maybe a free hour where I can sneak in a nap – my systems work on autopilot, telling me to brush them aside. The little voice inside my head will sometimes pipe up: “Yes, you have papers that need grading, but shouldn’t your son have fifty meal options for dinner, just in case?” The messaging gets confusing, and this ultimately hurts everyone else. You should definitely do work for your job, and when it comes to toddlers, falling asleep while playing with blocks means I get a rude awakening when they’re chucked at my head. Sometimes I need a reminder, often from my wife, to take care of myself as well.

Some distractions, like Bart’s algebra, we just can’t help but be tempted by. They fill our head and make us think they need to be done right this second. Giving everything a label of important vs not important rarely helps. By prioritizing things first, especially when helping others, has shown me what matters in my own life. Family first, always. Then myself, my career. Maybe, eventually, some day, my lawn will make it a little higher up the list.